Ten Thoughts on October’s CPI Report and the Role of Rents

Here are 10 thoughts on the October CPI report and the critical role of rents – now and going forward.

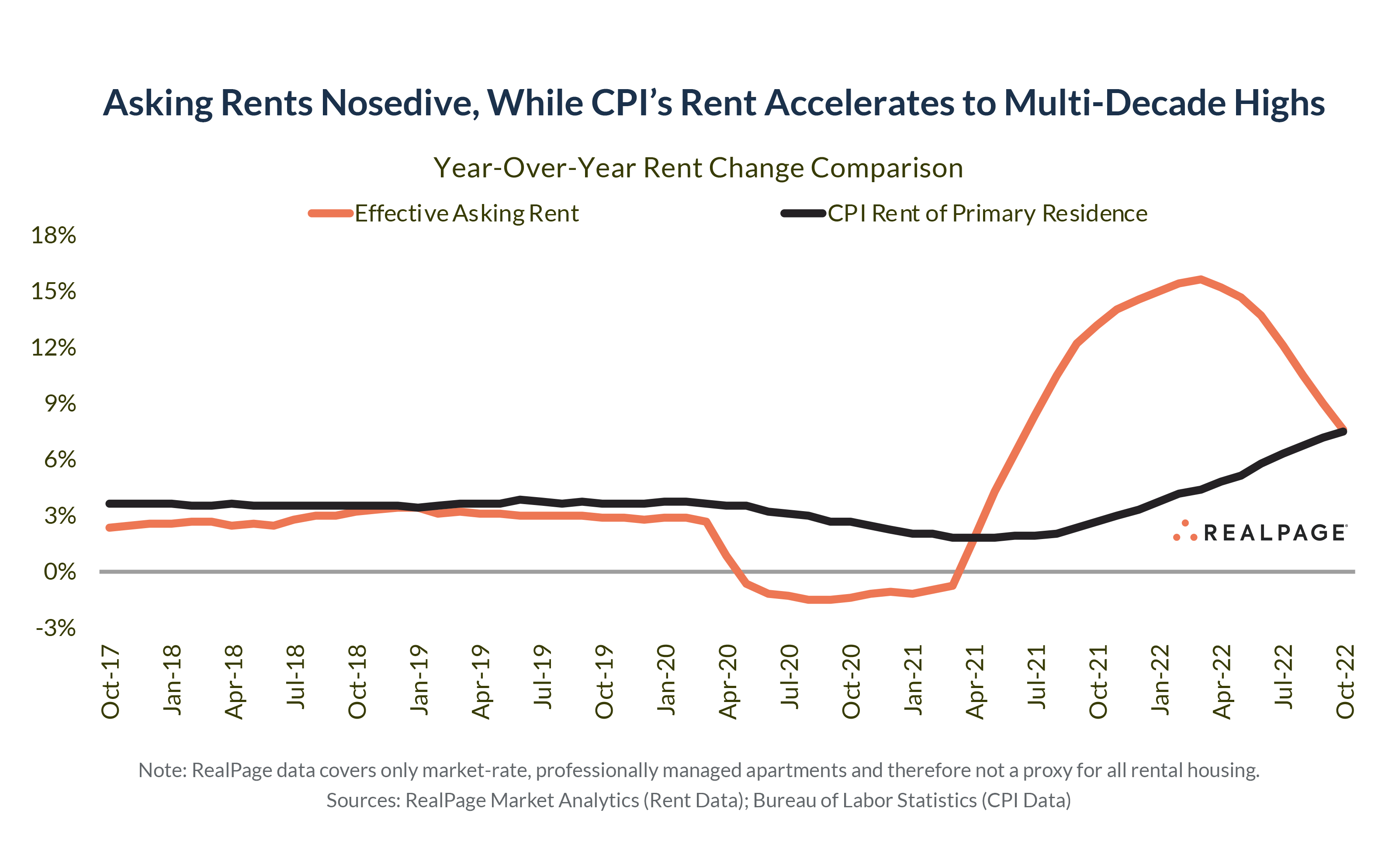

1. We continue to see CPI’s rent data lagging behind real-time rents – and not just for new leases. But since new leases are the early indicator, let’s start there: Note from this first chart that while market-rate apartment rent and CPI rent trends (YoY) are converging, they are both moving rapidly in OPPOSITE directions due to a well-established lag effect – an issue the Fed is, of course, aware of. (More on embedded/in-place rent in a moment.)

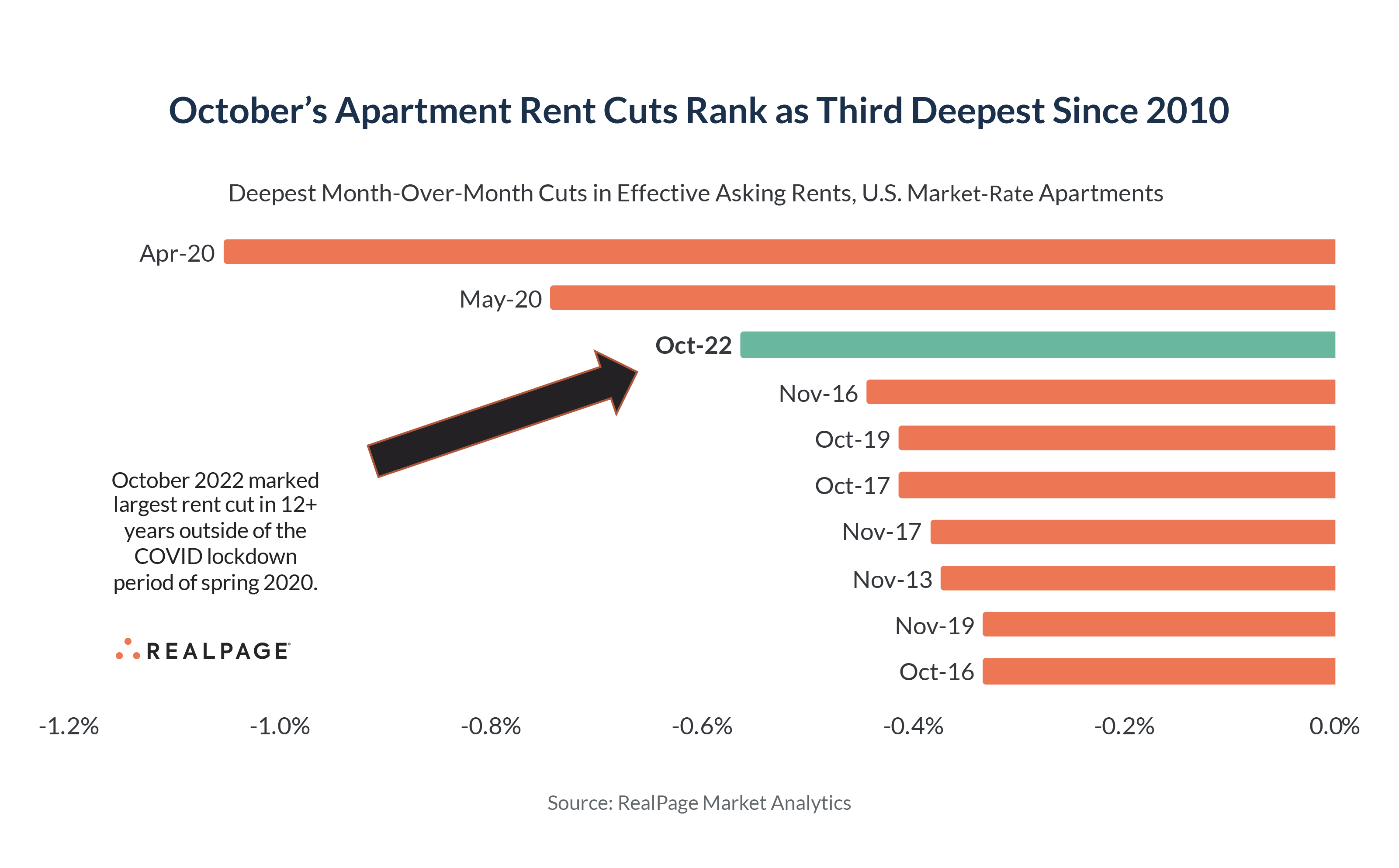

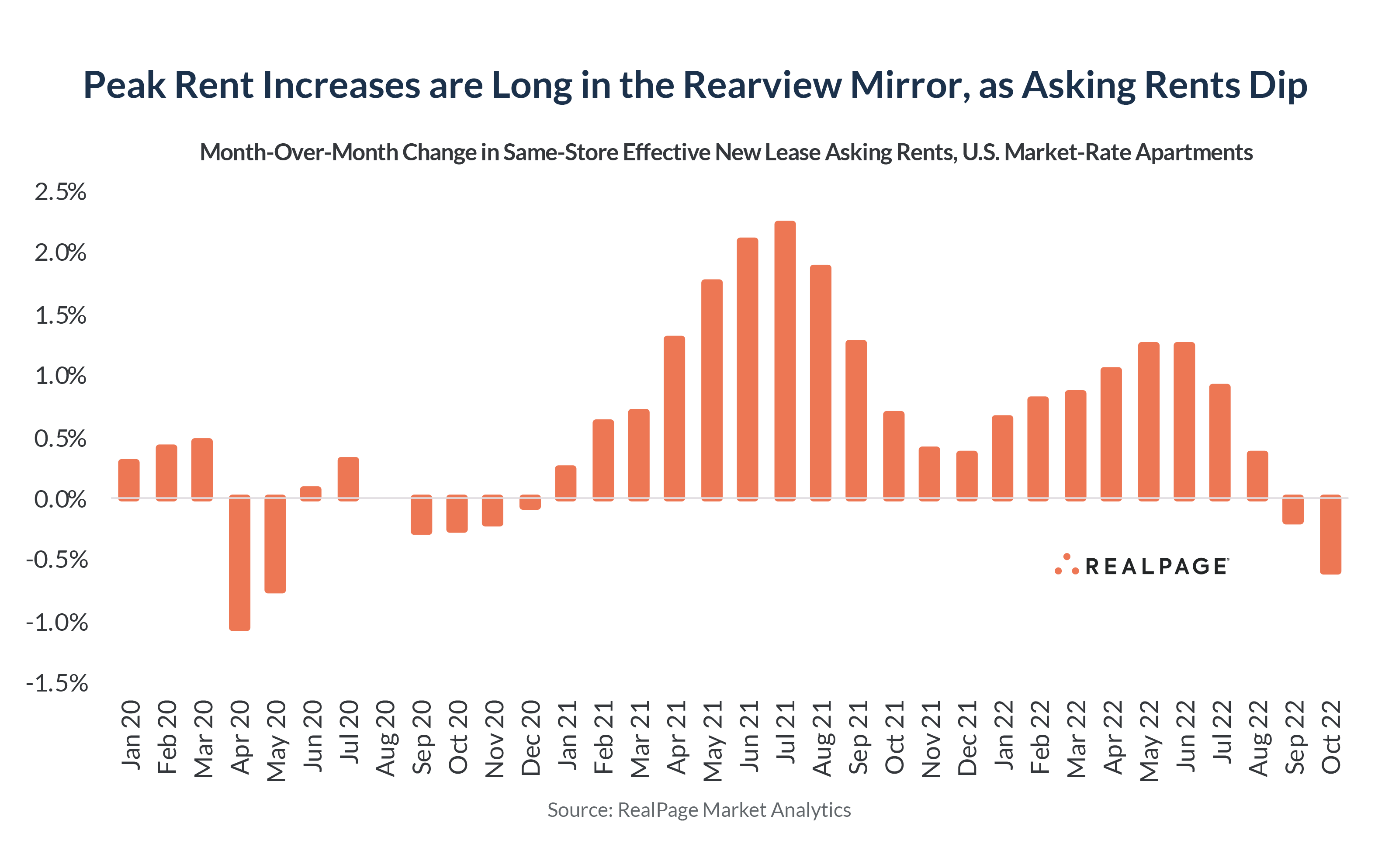

2. Asking rent growth month-over-month peaked in July 2021 for market-rate apartments, and renewal rent growth peaked one year later in July 2022. Vacancy has been rising since March, so rent growth is cooling significantly.

3. Month-over-month asking rents for new leases dropped in each of the past two months, and renewal rent bumps are shrinking (and will continue to shrink) as operators focus on retaining residents to protect occupancy and cashflow. As a result, embedded rent growth (or in-place rents) among market-rate apartments has peaked and turned.

4. Yet the CPI shows October saw a new peak in year-over-year embedded rent growth, fueled by a month-over-month increase just a hair below the multi-decade high recorded in September.

5. Rent is the single-largest variable in the CPI’s single-largest category (shelter, at nearly one-third of the weighting), and it’s cooling significantly, but it appears we won’t see that reality reflected in CPI until 2023 due to lagging data. Remember that the CPI’s rent survey is used not only to estimate renter costs, but it’s also the primary variable in estimating costs for the even larger homeownership category. One key difference – oddly enough – is that CPI’s rent measure includes utility costs, while its “owners equivalent rent” does not.

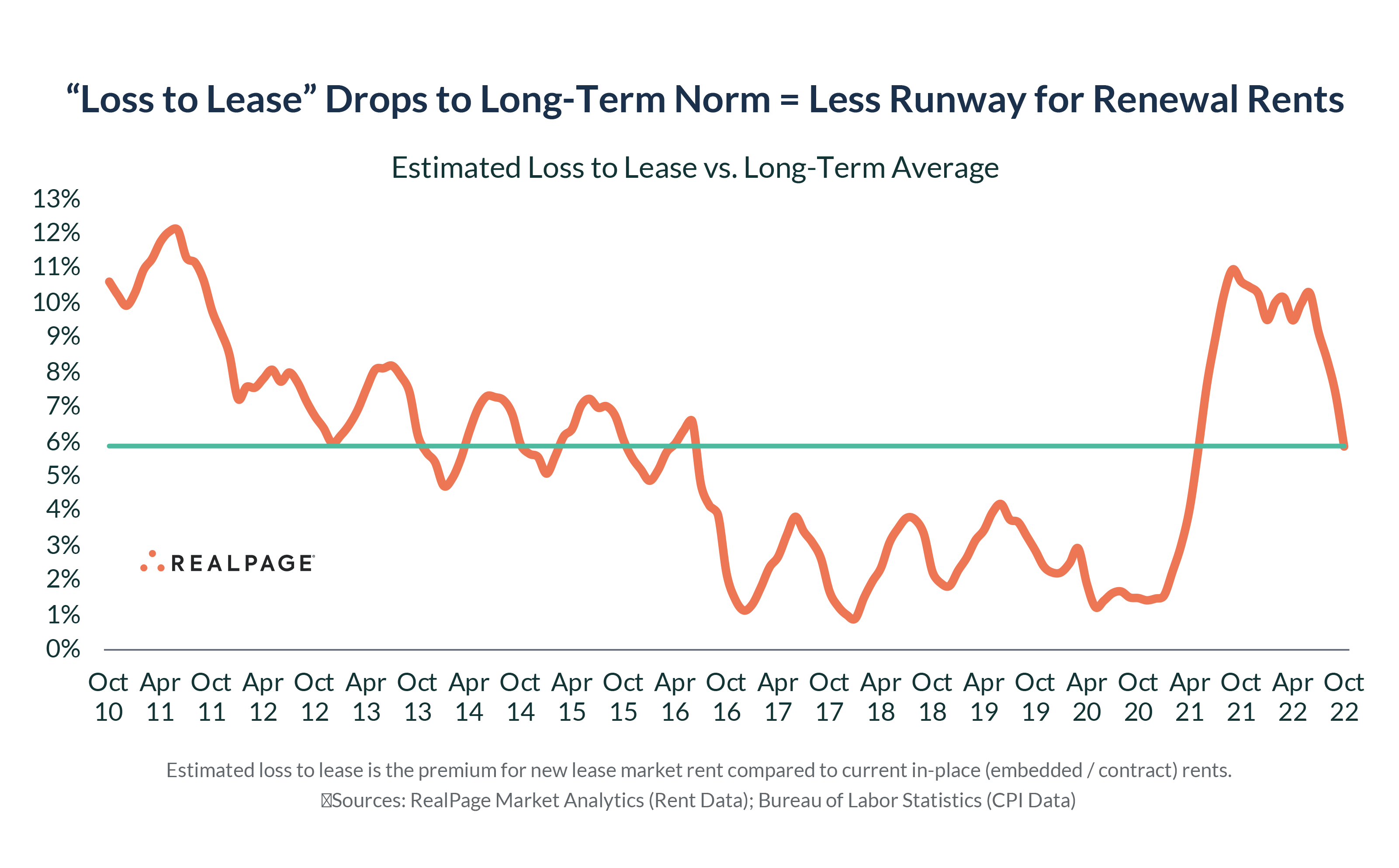

6. Yes, of course the CPI’s embedded/contract rents lag new lease rents. Fed knows this, too. But as noted above, the lag appears to be deeper than that. Here’s another data point to support that conclusion among market-rate apartments: the real-time data shows renewal increases are set to cool sharply due to shrinking “loss to lease” – the gap between market asking rents and embedded in-place rents. Loss to lease in October dropped back to the long-term average of 5.8%, down from more than 10% in June. That means there’s substantially less upside for renewal rent increases (particularly given that new lease demand and rents have cooled, making retention more critical).

7. Remember that if you want to move rents (as the Fed does), it starts with the asking rent for new leases. And that’s been happening. Asking rent growth (month-over-month) peaked in summer 2021, and it’s cooled throughout 2022. CPI is capturing a lagged indicator for rent, which is a big reason why it’s still going up as other CPI categories cooled off in October.

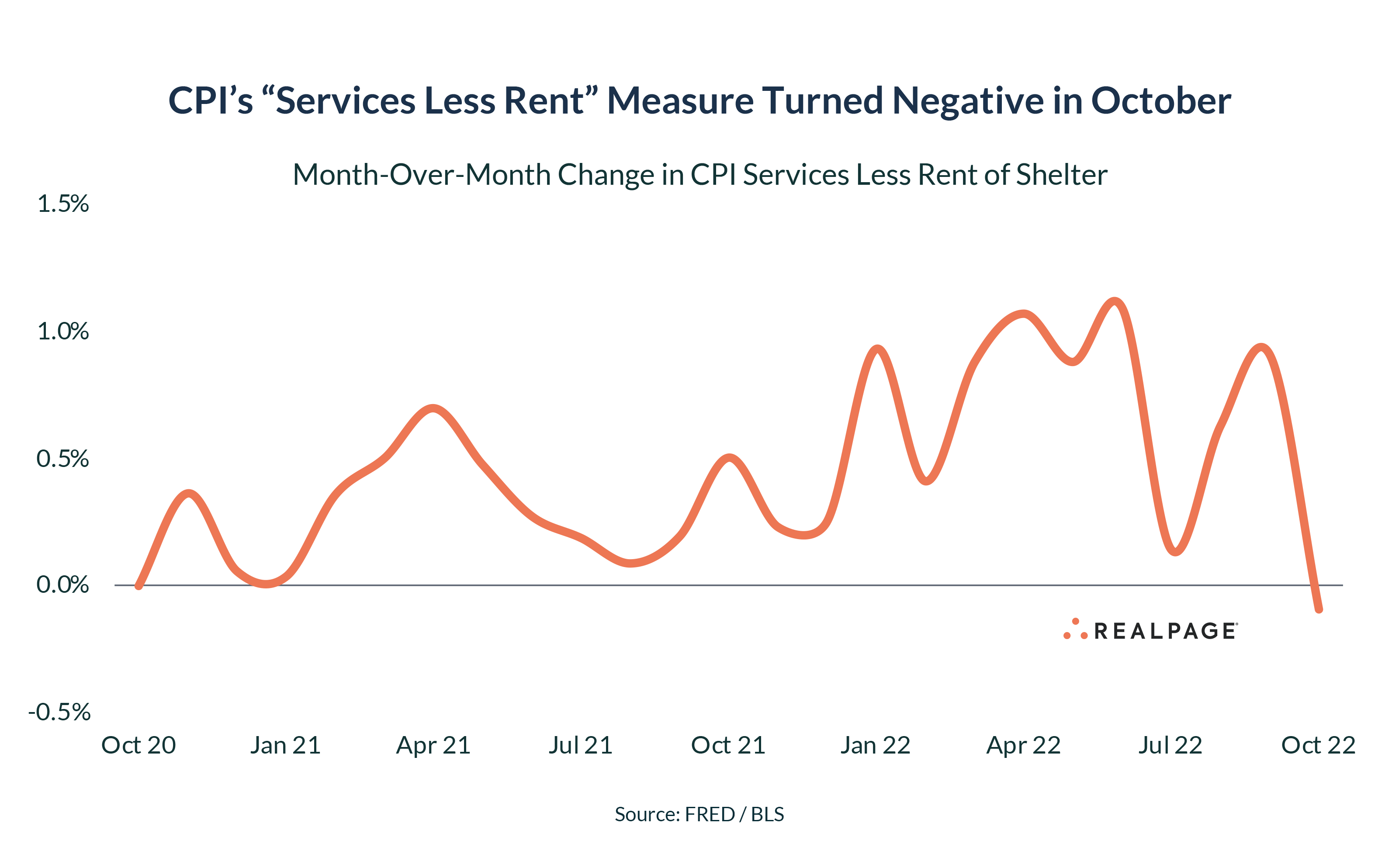

8. Super interesting to see CPI’s “services less rent” is actually DOWN in October. Imagine the impact if the CPI had captured more real-time data for rents, too...

9. The cynics will point out that this same lag played out in 2021 when rents were running up, and that’s true, but it was always a known issue, with studies having already established the lag prior to that.

10. Bottom line: For CPI to cool meaningfully, its shelter component must cool off. For shelter to cool off, rents must cool off. A rent cooldown will start with asking rents as the leading indicator – and that’s been happening throughout 2022. But CPI’s lagging methodology won’t capture this until sometime in 2023.