At the onset of the 2023 calendar year, there are more than a handful of datapoints that suggest student housing’s outlook is at its strongest relative position in many years. After all, the industry is just a few months removed from its highest-ever annual rent growth and occupancy reading. Equally important, the return to more normal university settings with in-person classes and extracurricular events back in full swing has brought with it a rejuvenated energy for operators within the space.

The tailwinds are a welcomed development after the doldrums of 2020 and 2021 created numerous questions for the industry’s long-term outlook. Still, risk accompanies any commercial real estate sector and student housing is no different. With that in mind, here are the five key trends RealPage is monitoring for the student housing performance outlook in 2023 (and beyond).

Recent Momentum Favors a Strong 2023 (and Likely 2024)

The start of the academic year in 2022 brought with it never-before-seen rent growth and occupancy. Rent growth surpassed 4% when weighted throughout the leasing season (with the August standalone reading achieving nearly 7%), according to data from RealPage Market Analytics.

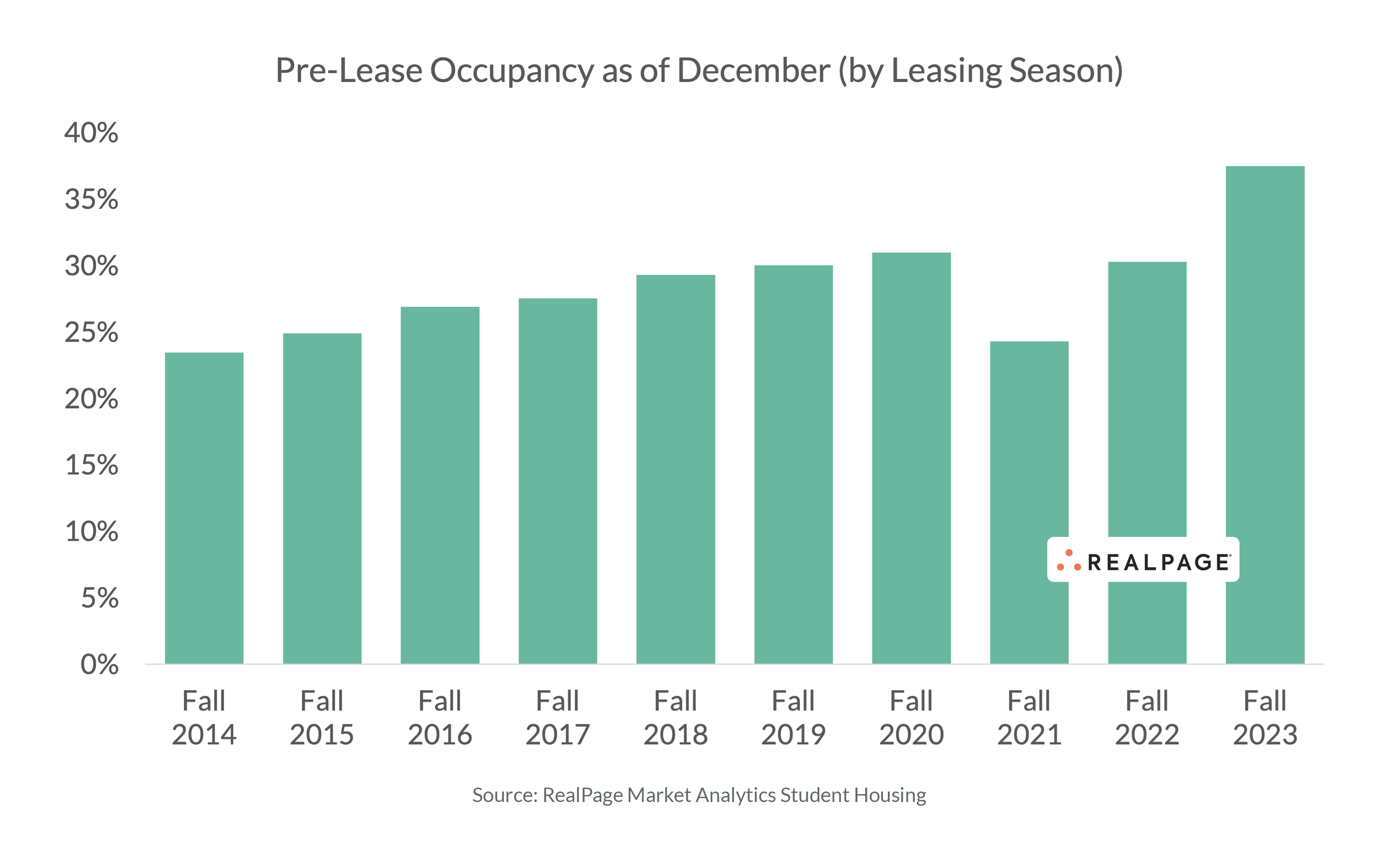

Fall 2023 performance has been equally striking. Pre-lease occupancy through December is easily at its highest mark on record for the month with nearly 38% of all beds already leased for the upcoming Fall semester. And remarkably so, 30 of the RealPage175 campuses have already leased more than 50% of their off-campus beds for the upcoming academic year. Four schools (UT-Knoxville, Angelo State University, the University of Arkansas and the University of Wisconsin – Madison) already sit at or above 90% pre-leased for the upcoming year).

From a strictly momentum-based perspective then, it’s difficult to see how the Fall 2023 leasing season runs out of much steam (barring a true black swan style event).

The Enrollment Outlook Yields a Mixed Bag of Results

One of the key reasons why performance for purpose-built off-campus student housing has been so excellent in recent months is that students have flocked back to campus.

Early indicators suggest that the much hoped for enrollment boom in the post-2020 period has indeed materialized. Students who took a year away from campus appear to have returned. Similarly, students who elected to delay their move to four-year universities whether by taking a gap year out of high school or by temporarily enrolling in a local two-year college have also returned. That compounded effect has resulted in a lot of housing demand.

The biggest beneficiary of the enrollment boom thus far appears to be the larger, established Power 5 (or Tier 1) campuses. Even pre-pandemic these campuses were garnering the lion’s share of national enrollment growth.

But specific to the past two years, it appears that many students took a chance and submitted applications to their dream Power 5/Tier 1 school with the hope of eased admission standards playing out. Indeed, the relaxed admission standards among these schools means the bigger wave of applications – and more importantly, more accepted applications – has created an additional boom effect for these campuses.

Once more, though, the outlook isn’t totally risk free. The growth rate of the nation’s 18-to-24-year-old cohort has slowed quite notably below early 2010s standards. That coincided with the huge enrollment boom in the 2010s more than the Great Recession, as further supported by National Multifamily Housing Council (NMHC) research.

Questions also loom as to whether the pace of international enrollment will continue to grow at its pace seen in the 2010s decade. While the share of total U.S. enrollment explained by international enrollment remains relatively modest, there are campuses in select areas where international enrollment shifts could dictate overall enrollment levels.

Construction Has Eased … But There are Other Factors to Consider

Student housing deliveries have been generally trending downwards since 2019. Prior to that point, the nation averaged roughly 50,000 beds delivered per year with some variation between the 2010/2011 lull and the 2014 to 2016 peak.

Deliveries pulled back even further in 2021 and 2022 as the pandemic halted many new project starts. In Fall 2023, the data suggests an increase in new deliveries above the 2021/2022 trough. Still, an anticipated annual delivery total of roughly 40,000 beds remains well below the 2010s-decade norm.

That pullback in construction can be seen as a positive for campuses where new deliveries have been the most aggressive. One of the challenges with purpose-built student housing assets is that they are exactly that – purpose built. And if the balance between total available students enrolled at a university gets too watered-down by available housing product, then performance can falter and take some time to recover.

For example, these campuses are the nation’s most highly concentrated in terms of available off-campus student housing beds relative to enrollment.

Bear in mind that this is only the off-campus purpose-built bed count and doesn’t factor in things like available on campus housing nor the “shadow market,” which could be either conventional multifamily housing, single family rentals or Greek Life residences.

Therein lies a mid-to-long-term unknown. Just exactly how much does on-campus housing compete with off-campus housing? How does an increase in vacancy among shadow market options such as nearby conventional housing or single-family rentals impact student housing occupancy – especially in the event that student housing property counts continue to increase even if at a slower rate?

All considered, it’s likely that demographic trends, limited site availability (many of the most desirable locations at the most desirable schools have already been built), and external economic factors such as the growing challenge of securing development loans in a high interest rate environment will dictate fewer beds delivered in the 2020s decade than the 2010s norm.

On-Campus Housing – a Threat, a Complement, or a Non-Factor?

Much like enrollment, on-campus housing can be best viewed as a mixed bag of results. From one perspective, on-campus housing serves a very specific niche need as on-campus living requirements exist at most schools. In that regard, on-campus housing is a complement.

The threat of on-campus housing is that some more highly amenitized public/private partnership (P3) developments could poach some off-campus housing demand. But more importantly, some degree of off-campus demand is at the mercy of university administrators and any adjustments those administrators make to on-campus living requirements.

Should more on-campus housing deliver through means of P3 relationships, there could be some pressure for extended (i.e., second year) on-campus living requirements.

One potential benefit that off-campus housing could see from on-campus housing is that – perhaps counter to the broader narrative – on-campus housing rents have actually risen at a faster rate than off-campus housing.

Summary

All considered, the student housing outlook can likely be best understood through one of two lenses.

The first lens would be short-term (one- to three-year) outlook. That outlook appears to be in solid shape due to the previously mentioned factors.

The second lens – the long-term outlook (five-plus years) – has a lot of unknowns. But at minimum the challenge of a slowing 18-to-24-year-old population growth is a critical headwind.

Lastly (while more of a qualitative factor than something that can be analyzed through quantitative means), there is some additional downside risk to enrollment growth in light of rising cost of attendance coupled with the perceived value of a four-year degree among the younger generation that will become future university students – and potential student housing renters.