Hurricane Ian flooded, destroyed or damaged an untold number of homes, particularly in Southwest Florida. The full impact of the deadly storm has yet to be measured. But what can past hurricanes tell us about the potential impact to the apartment market?

One of the more recent examples is Hurricane Harvey, which flooded much of the Houston metro area and displaced thousands of residents in August 2017. We could see similar impacts in Southwest Florida as we saw back then in Houston.

Vacant Units Will Fill Up Fast

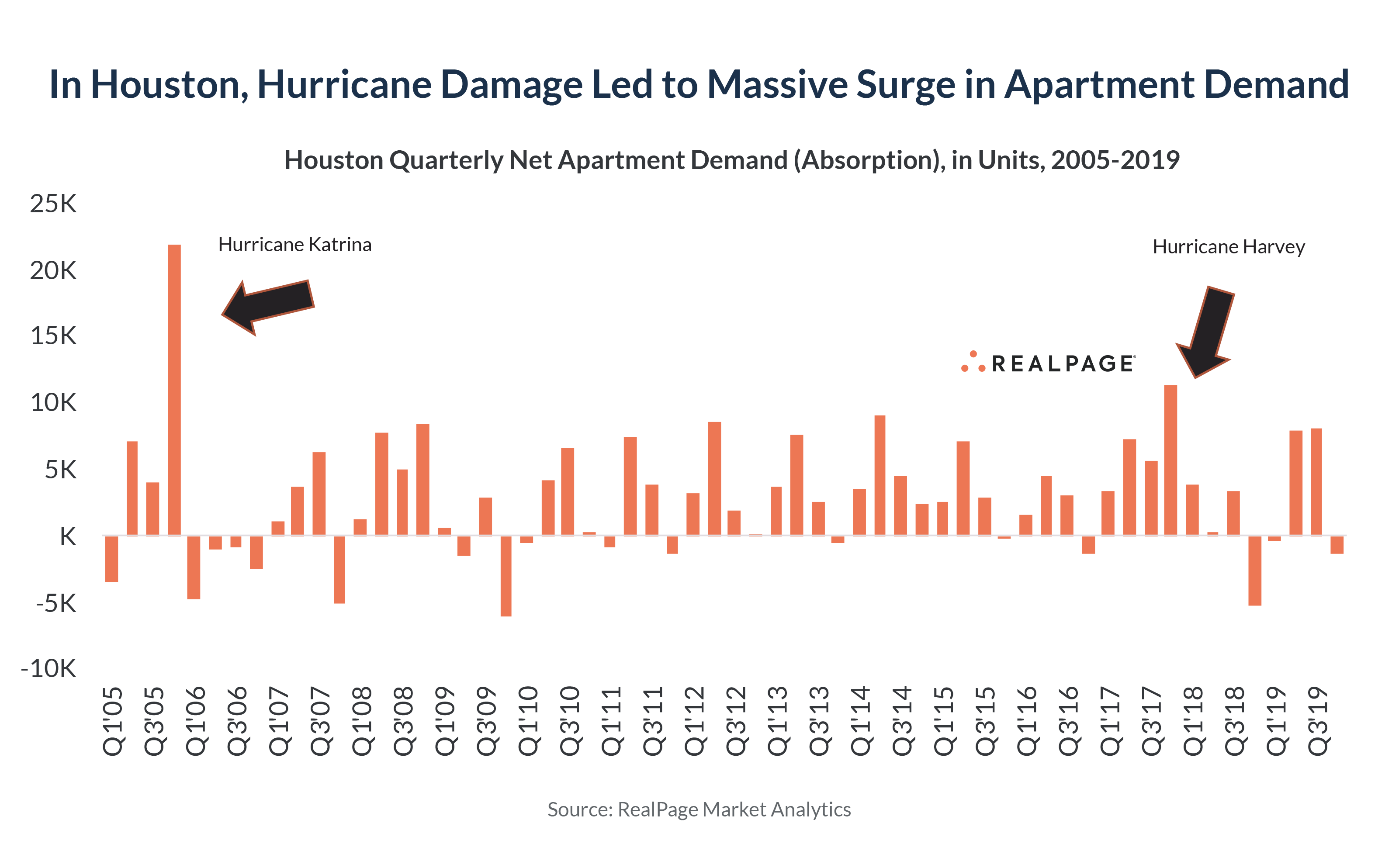

History shows us that after a major storm, vacant rental units fill up fast. Displaced households need a place to live. After Harvey hit, Houston saw a huge surge in apartment demand. In fact, the more than 11,000 units absorbed in 4th quarter 2017 ranked as the metro’s second-largest ever (at the time). The top quarter ever in Houston for apartment demand? That was back in 2005, when Hurricane Katrina evacuees migrated from New Orleans.

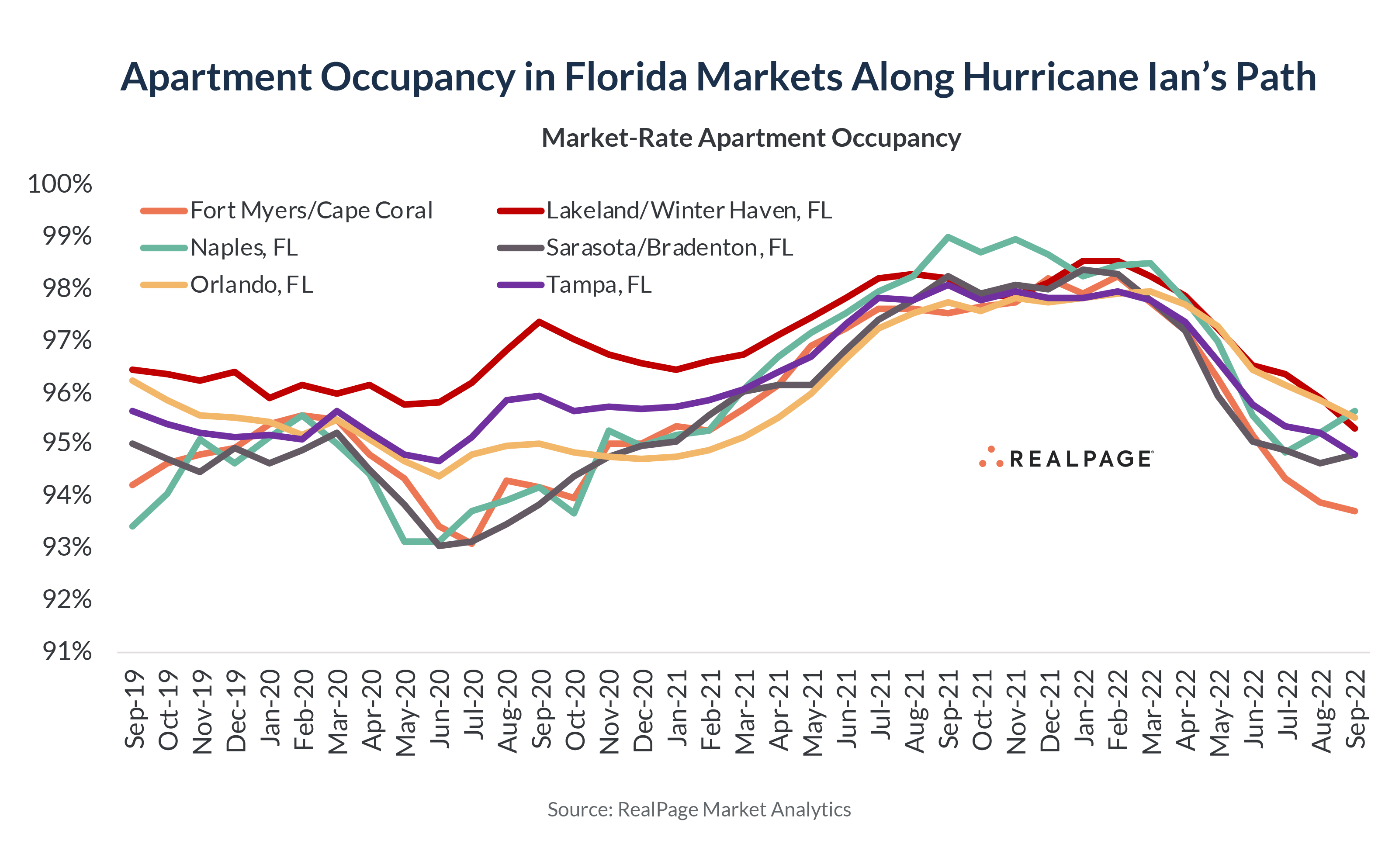

While the total number of households displaced by Hurricane Ian are not yet known, you can expect demand for vacant units from displaced homeowners and renters alike. That’ll likely reverse a 2022 trends of declining occupancy rates across Florida – at least temporarily.

That’s a bit of good news: There are more apartment vacancies today available for displaced households than there would have been had the storm occurred a year ago. After COVID hit, Florida markets saw a big spike in apartment demand from the work-from-anywhere and live-anywhere crowd relocating to the state, taking occupancy rates to ultra-high levels. But 2022 brought a big shift in momentum, erasing some of those gains.

Prior to Ian, Fort Myers (where much of the damage was centered) was one of the fastest-cooling apartment markets in the country. Occupancy there dropped 3.8 percentage points year-over-year (the largest drop among the nation’s 150 largest metros) to a rate of 93.7% as of September. Sarasota/Bradenton, Naples and Tampa also ranked in the top 10 for the biggest occupancy drops over the last year, each seeing declines exceeding 3 percentage points.

Prior to Ian, Fort Myers (where much of the damage was centered) was one of the fastest-cooling apartment markets in the country. Occupancy there dropped 3.8 percentage points year-over-year (the largest drop among the nation’s 150 largest metros) to a rate of 93.7% as of September. Sarasota/Bradenton, Naples and Tampa also ranked in the top 10 for the biggest occupancy drops over the last year, each seeing declines exceeding 3 percentage points.

How far out will that demand reach? That’s not yet clear. We’d expect most of that demand to come in and around Fort Myers and Naples, but it’s not yet known how many apartment units will be taken offline in those areas due to damage. Additionally, some apartments in the Orlando area were flooded as well, so at least some demand could stretch north.

Displaced Residents Will Look for Short-Term Leases

Storms obviously create temporary demand from displaced households, particularly from homeowners needing to repair their homes or relocate to new homes. When Harvey hit in Houston, that temporary demand surge lasted about six months.

Such a demand surge would typically result in big rent hikes under normal circumstances. But after Harvey, we saw many apartment operators waive premiums for short-term leases to accommodate that surge of short-term demand. We also saw effective asking rent growth for new leases in the Houston metro area stick at around 4% year-over-year, reflecting that many operators voluntarily capped rent increases.

We’ll likely see many operators take a similar compassionate approach in Florida.

Note that because much of the demand comes for shorter-term leases, hurricanes ultimately provide little (if any) structural lift for the apartment market. Apartments will temporarily fill up, and then give back most of those gains. We saw that pattern play out after Harvey in Houston, with significant move-outs in the latter part of 2018. Additionally, short-term leases create more unit turns – and that means more turn costs (which is why shorter-term leases come with premiums).

But most apartment operators recognize their role as essential providers after a storm, and likely will give little thought to those issues while focusing on serving the needs of displaced Floridians.