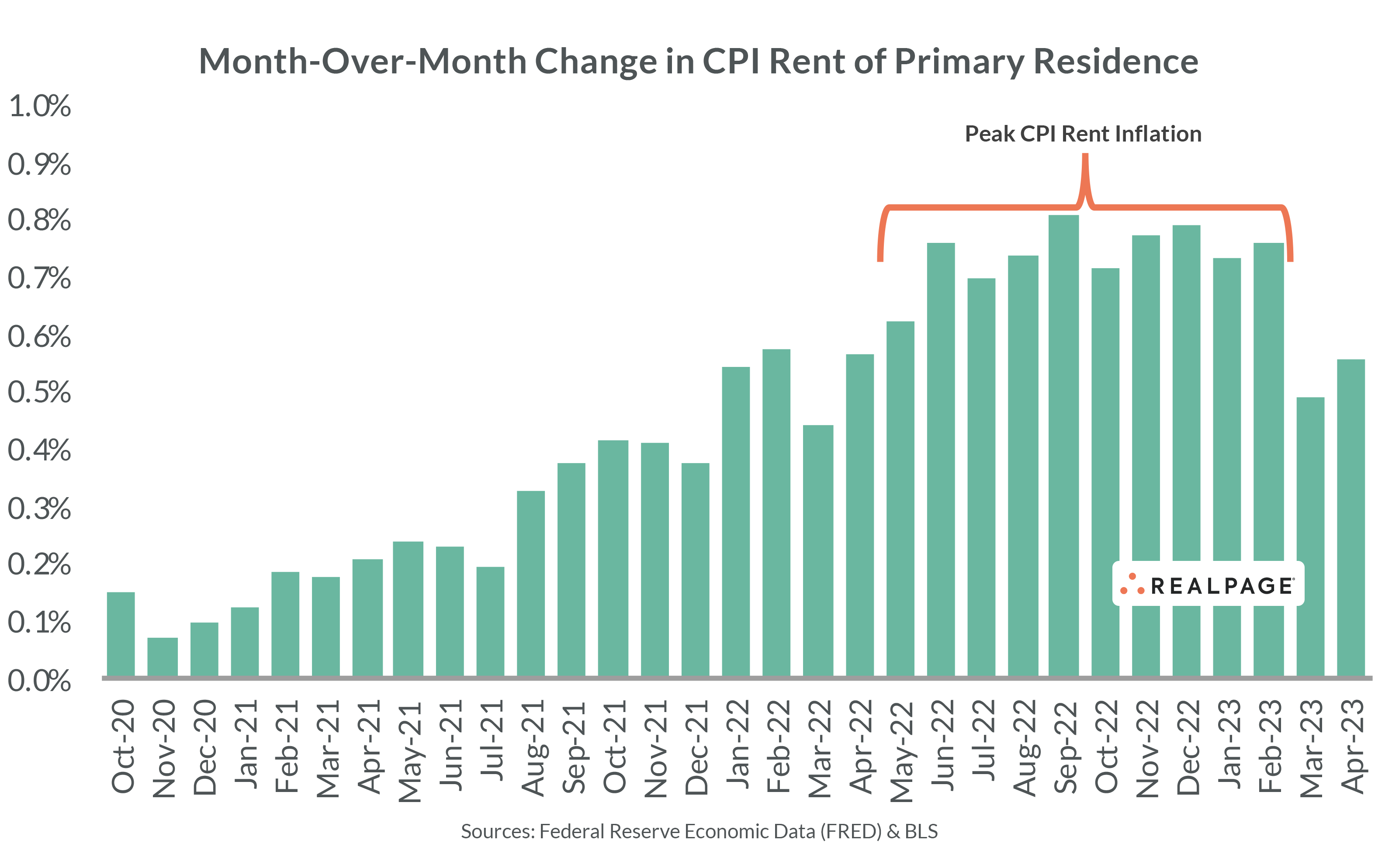

If you squint closely enough at the Consumer Price Index’s rent data for April, you’ll notice something critically important: Rent growth (as measured by the CPI) cooled for the first time in two years ... and right on schedule.

Several studies have shown a 12-month lag effect between asking rent growth and CPI’s “rent of primary residence” metric.

Sure enough, right on schedule, it appears CPI rent growth peaked in March 2023 – exactly 12 months after RealPage asking rent growth data peaked in March 2022. The drop from March to April wasn’t much – from 8.81% to 8.80% – but it’s the direction that is most notable. For context, asking rents showed a similarly miniscule drop from March to April 2022, and since then, it’s plunged precipitously. The same should happen with CPI rents.

This is a big deal for inflation and rate watchers (including apartment investors) because rent is the largest variable in the CPI’s largest category: shelter. Remember: The same rent survey used to estimate rent is also the primary variable used to estimate homeowners’ costs. So while homeowners are weighted more heavily than renters, it’s the same core dataset.

The lag effect is widely known among economists and by the Fed. Real-time rents started cooling off as housing demand started waning late last spring. As we’ve been saying for a while: Rent has been a heavy anchor on the CPI, preventing deeper cooling in the official inflation measure.

Rent is unique in that – unlike groceries or gas, for example – the CPI does not use current pricing (the asking rent for a new lease) and instead tries to measure the contract rent (which would only change once per year per renter on a 12-month lease).

The good news is that CPI rent inflation is highly predictable because it will follow the path of asking rents. Contract rent is impacted both by new and renewal leases; however, the asking rent for new leases effectively serves as a cap on renewal leases. Asking rents are highly transparent online, which gives renters renewing leases visibility into current pricing and, in turn, means property managers avoid sending renewal offers above the new-lease asking rent. Furthermore, property managers routinely price renewals below new leases (since they can avoid turnover and vacancy costs with a renewal).

Additionally, rising vacancy and new supply mean that renters today have far more options than they did in 2021 and early 2022 – which puts further downward pressure on rent growth.

Bottom line: Peak rent growth is unquestionably in the rearview mirror.

So what does the path forward look like for CPI’s measures of rent and shelter? Well, CPI’s month-over-month rent data showed its biggest spikes between May 2022 and February 2023. It’s highly unlikely those numbers will be matched, so as each month rolls off the 12-month change calculation, we’ll see CPI’s year-over-year change number cool. By spring 2024, it should be back in the normal range – or very close to it.

Barring an economic shock or some weirdness in other categories of CPI, inflation should continue to drop off over the next year – no matter what happens with rates or with jobs – simply because the largest variable (rent) in the CPI’s largest category (shelter) is on a predestined down ramp.